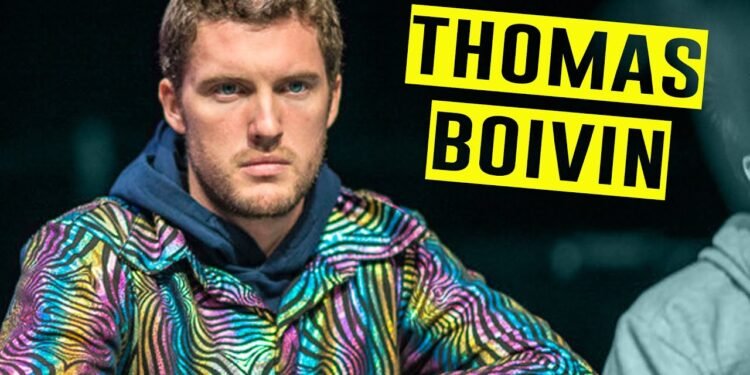

Brussels, (Brussels Morning) – In his Belleville, Thomas Boivin did not photograph the Paris of the Grands Boulevards but the Paris of young people, offering a colourful black and white palette to a generation that is much talked about but rarely shown.

At a certain time. Edith Piaf, Django Reinhardt and Maurice Chevalier lived in Belleville. Today, Belleville is still a district renowned for its nightlife, its many bars, guinguettes and its park on a hill offering a beautiful view of the city from the northwest. Belleville has always been a mixed neighbourhood, transformed by successive waves of immigration, explains Boivin, who began photographing his neighbourhood in 2010. What was important to him is that the neighbourhood does not look like the centre -city. “Even if there are large parks with open spaces, this is not the Paris of the grand boulevards,” says BRUZZ.

Photographers have long struggled with the heritage of Brassaï and the humanist photography of the 1950s, which repeatedly portrayed the public and night life of the City of Light. “For a long time, Paris was little photographed, precisely because a whole generation of photographers no longer knew what to add to this heritage. The streets had not changed. Personally, I thought about it as little as possible, while making sure not to reproduce images that were already part of our visual memory. The portrait of the neighbourhood where he lived for a long time, he describes it more as a question of avoidance than a need for contrast. “My photography is closer to North American street photography than to how my notable predecessors photographed the city in the 1950s. Today, Paris is one of the most multicultural cities in Europe. In terms of diversity, the suburbs of Paris are more like Atlanta, for example. He cites, among other sources, black and white photos of ordinary people by Mark Steinmets or Judith Roy Ross as inspiration. But not all of its heroes come from the United States. He also mentions the French photographer Patrick Faigenbaum, the Japanese Issei Suda, the British Chris Killep and the Dutch Rineke Dijkstra. But not all of its heroes come from the United States. He also mentions the French photographer Patrick Faigenbaum, the Japanese Issei Suda, the British Chris Killep and the Dutch Rineke Dijkstra. But not all of its heroes come from the United States. He also mentions the French photographer Patrick Faigenbaum, the Japanese Issei Suda, the British Chris Killep and the Dutch Rineke Dijkstra.

The heritage in question partially explains why buildings are rarely seen in Boivin’s photos. The grandeur of the capital seems to have been replaced by the people, above all young people, who populate the streets. The photographer describes them as a generation that exudes self-confidence, generosity and accessibility, but which is depicted so little, even if it is included in all the major analyses of society. “I see an emotional power in showing the faces of this younger generation, especially at a time when they are talked about so much. But for him, Belleville is not a series of portraits, but rather a walk. The work is part of his world and incorporates elements of the environment and details of public space that struck him during his walks in the neighbourhood. This is also the biggest difference with respect to the series Place de la République series , a work in progress, started during the pandemic and exhibited for the first time in Brussels. “As there are always people in this square, I had to isolate the young people and photograph them much closer. This was only possible with a tripod and taking pictures from a fixed position. »

His updated view of Paris shows life as it really is. Organized grandeur is replaced by a more innocuous side, a look that is at first glance more furtive and random, in appearance. “In my photos in Belleville and Place de la République, it’s not just about the place, if you know what I mean. Despite territorial and stylistic boundaries, Boivin paints a portrait of a universal city, which indirectly conveys the speed at which everything is changing, without necessarily setting aside the nostalgic and romantic gaze historically linked to the city. “Recently, someone told me that my photos of Belleville look old, while the last photo was taken less than two years ago… It shows the speed of gentrification,” the photographer concludes.