Belgium, (Brussels Morning Newspaper) With the recent passing of Queen Elizabeth II, it would be hard to find a woman throughout history who has been more celebrated. For 70 years, Queen Elizabeth has been at the forefront of public attention as her life, her impact, family, and now her demise was there for public consumption.

Just for the sake of conversation though, what other women can we name who have been as memorialized? Certainly, Mary, the mother of Jesus, would have to be part of that discussion. Her likeness can be found in just about every corner of the Christian world. Cleopatra perhaps? Joan of Arc? Catherine The Great? Mother Theresa? This article directs your attention to a woman who has been honored and memorialized in a thousand different ways yet her legacy remains under the historical radar. Interestingly, her backstory is very Belgian-specific. Consider…

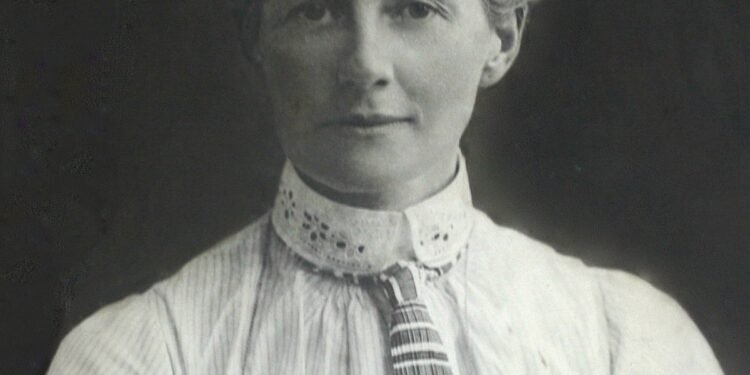

Edith Cavell was born (1865) in Norfolk, England where her father was a local Anglican vicar for close to fifty years. As a young girl she served as a governess to wealthy Brussels family but returned to London to receive professional training as a nurse. In 1907 she was recruited back to Belgium by Antoine Depage— the founder of the Belgian Red Cross— to organize a newly established nursing school in Ixelles, Brussels. Edith began to publish the professional medical journal L’infirmiere (still in circulation), train nurses for multiple Brussels hospitals, schools and clinics. She was prolific! Depage said of Edith Cavell: “she is an integral part of the growing people in the medical profession in Belgium.”

With the outbreak of World War I and the German occupation of Brussels (Nov.1914), Edith began treating wounded Belgian, French and even some Germans soldiers and civilians. She also began harboring and funneling out of occupied Belgium, many of the wounded resistance fighters. Edith was outspoken and did not make any effort keep her actions covert. In August of 1915 she was arrested in violation of German military code for “harboring Allied soldiers”. With complete honesty, she never denied her actions. Her lack of remorse effectively signed her own death warrant. She was court-martialed, found guilty and horrifically executed by firing squad (Oct.12,1915) in Schaerbeek. Her last words showed her complete conviction: “Standing as I do in view of God and Eternity, I realize patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred and bitterness towards anyone…tell my loved ones that my soul is safe”.

Edith Cavell’s last words were not those of one who sought to be a martyr. Yet in the fog of World War I, that is precisely what she became. Public outrage was immediate as her execution received extensive press coverage and international condemnation. She would become an iconic propaganda figure and helped to increase morale for the Allies. Hugh S. Gibson, The United States Ambassador to Belgium for example, wrote that the sinking of the Lusitania (May,1915), the Burning of the University of Louvain (also known as The Rape of Belgium), and the execution of Edith Cavell would collectively “stir all civilized countries with horror and disgust towards the aims of the German aggression.”

The impact of the Edith Cavell’s execution cannot be understated. Dozens of hospitals throughout the U.K., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the U.S.A have since incorporated the name of Edith Cavell into their nomenclature. In Belgium the Centre Hospitalier Interregional Edith Cavell operates a group of five hospitals in and around Brussels. The Edith Cavell Medical Centers (there are five) still operate today. Additionally, many of these hospitals in Belgium and abroad offer nursing scholarships in her name.

Edith Cavell’s life and times have been fertile ground for the film, television, theatre, and music industries as well. Silent films such as Nurse Cavell (1916) and The Price She Paid (1924) followed soon after her death. On stage, Nurse Cavell became a popular 3-act play which ran for 34 performances at the Vaudeville Theatre in London (1916). Television is no stranger to Ms. Cavell’s story either. The BBC drama series The Crimson Fields (2014) and the Belgian T.V. show Les Plus Grandes Belges (2005) have Edith Cavell themes. In opera, a 3- act melodrama entitled Edith Cavell premiered at the Royal Opera House in Valletta, Malta in 1927. In popular music, Que Sera (by O’Hooley and Tidrow,2010), Saint Stephens End (by Felice Brothers (2008) and Amy Quartermaster (by Manning, 2011) collectively seek “to portray the horrors of war from a woman’s perspective and explore the feelings, sounds, and senses as she stood before a firing squad”.

The namesake of Edith Cavell can be found in various schools ranging worldwide from India to Bolivia, Malaysia to Argentina, and Jamaica to South Africa. Her memorial statues adorn cemeteries, churches, through the U.K. and North America, Czech Republic and even in Germany. In Brussels, her likeness can be found in many statues and memorials throughout the city. In 2005 a bust of Edith Cavell was unveiled by Princess Astrid of Belgium in Montjolie Park in Uccle.

To be memorialized in hospital, music, movies and schools is only part of Edith Cavell’s legacy. Other disparate entities such as: car parks, playgrounds, gardens and bridges throughout the world are named after her. A peak in Western Canada (Mount Edith Cavell Peak elevation 3,363 m.), a champion racehorse in America, a variety of rose flowers, a commemoration stamp in England all pay tribute to the heroic nurse Cavell. Even a cosmic cloud cover (a corona) over the plant Venus has been named after Ms. Cavell.

Inarguably, the quintessential likes of Queen Elizabeth, The Virgin Mary, Joan of Arc et.al., are widely recognized historical icons — and for good reason. Collectively, their impact has been celebrated and esteemed for centuries. To say the very least, Edith Cavell’s legacy has cast a wide and varied influence over our culture. Indeed, the case could be made to include Edith Cavell in any discussion of history’s most prolifically memorialized woman.

R.I.P. Edith Cavell…