Belgium, (Brussels Morning Newspaper) Like all species, wolves and other large carnivores play a vital and irreplaceable role in ecosystems, shaping habitats, biodiversity, and population dynamics. However, habitat loss due to urbanisation, lack of wild prey, and human hunting of these animals have for decades and even centuries wiped out these species across Europe, threatening their survival.

Farming has changed over the decades and traditional herding practices that protected farmed animals, such as shepherd supervision, guardian dogs, and night-time sheltering, were progressively abandoned. Simultaneously, the phenomena of rural exodus meant that large carnivores could explore new territory, but in cases where humans made a return, conflicts of coexistence arose.

Regarding wolves in particular, in recognition of the extinction threat, across Europe conservation efforts were put in place in the 90s to try to counter it. In 1992, through the Habitats Directive, rules were implemented to prohibit all forms of uncontrolled capture or killing of wolves in the wild, while still allowing for culling in a regulated and supervised way (article 16). Granting this formalized and strict legal protection status enabled the species to slowly repopulate in many areas where its survival was once compromised.

However, all these conservation efforts might now have been in vain. On November 24th, the European Parliament passed a resolution aiming to downgrade the protected status of wolves and other large carnivores, paving the way for an uncontrolled culling of these animals.

More specifically, the critical text calls for the Commission to assess populations with a view of adapting the protection status if the desired conservation status is reached – an amendment supported by the usual conservative political groups ECR, EPP and a large faction of Renew Europe, based on false unscientific narratives and pressure from hunter and big farmer lobby groups.

While the Greens/EFA political group recognises that in highly populated continents like Europe the coexistence with large carnivores can cause conflicts with human socio-economic interests, we have also listened to science regarding best practices. Therefore, during negotiations for this resolution we defended that the Commission should stand by the present level of protection for wolves, and promote coexistence through non-lethal solutions to conflicts, which have proven to be effective when applied and when MS have been bothered to fund them (EU funding streams already exist for this purpose).

The unscientific narrative sponsored by the groups that supported the resolution fails to portray accurately ecosystems’ dynamics and to focus on correcting Member-State’s (MS) insufficient or erroneous conduct.

Coexistence is possible

The line of our political group is that the Habitats Directive should not be opened to lower the protected status of these animals and that the already existing flexibilities for MS within article 16 of the Habitats Directive (to cull in a supervised and regulated way) should be used by them.

Successes in the reduction of livestock depredation have been attributed to actions taken for adaptation and prevention. As farmers must not be left to pay the costs of species’ conservation, we insist on public funding, via EU and national funds, for adaptive and preventive measures for coexistence, including generous and fair compensation, insurance, investments and others in order to protect farms, especially extensive upland pastoralism. Examples of such preventive measures include guarding dogs, electric fences, and human supervision in the field and virtually.

It needs to be highlighted that funding opportunities for coexistence already exist (for example via CAP, LIFE+, and EU State aid rules) and that many times the problem resides in the fact that the Member State is simply not allocating (enough) funds. In these scenarios where government support lacks and bureaucratic barriers persist not all farmers, especially small and medium-sized ones, have sufficient resources to adapt the farm themselves. Farmers’ compensation for losses and adaption costs must be fully covered by public funds, and access to these needs to be improved by MS and regions. Furthermore, public authorities must take notice of guidance developed by the Commission on this matter.

For MS, it is certainly easier to give a free pass for the shooting of these animals than to sit down, develop an integrated approach, and make funds available to provide farmers with the needed financial support and know-how. This free pass, however, would only mean that the extinction brink would come back in a few years and that the species would need protection again. A ridiculously ineffective cycle that can only be broken if we apply preventive and adaptive measures for coexistence.

Higher wolf population density alone does not necessarily correlate with more depredation of farm animals

Studies have indicated that large wolf populations do not directly correlate with high livestock losses. In fact, higher depredation levels correlate with unprotected/unsupervised husbandry systems and free-ranging livestock, and/or low densities of wild prey (which is a wolf’s preferred food even when domestic animals are abundant). Furthermore, it should be taken into account that many countries where annual depredation rates are very low also have substantial large carnivore populations, indicating that depredation can be lowered if livestock is suitably protected and supervised.

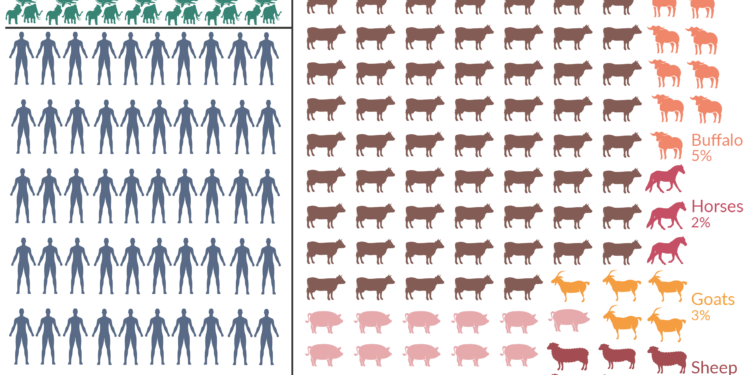

In addition, when discussing this problem, it should not be hidden that the impact of the depredation by large carnivores on farmed animals is relatively low when compared to mortality by other causes such as disease, husbandry, or climate. For example, studies have found that the upper estimate of depredation of sheep by wolves, dogs, and dog-wolf hybrids is 0.06 %, 0.004 % by bears, and 0.001 % by lynx; and by contrast, other forms of sheep mortality were found to be between 2.5-35.8 %.

Culling has proven to be at best ineffective… and at worse it can increase depredation

What the political groups that voted in favour of this resolution want is to see the killing of wolves unregulated so that shooting comes with no consequences. Nevertheless, wolf culling has proven to be ineffective to counter farm animal depredation, especially when it comes to established packs. In the worst case, it has been found that farm animal depredation increases following culls due to the pack dynamic being destabilised or divided (e.g. lone wolves), or new unhabituated packs moving in to fill a niche.

Wolves and other large carnivores are part of European ecosystems and have coexisted over millennia with traditional pastoralism. As humanity, we have reached a point where we have gotten used to controlling nature whenever it becomes inconvenient for our economic interests, even in cases where our conduct propels the problem. We exhaustively hunted the prey we had in common with these large carnivores and gradually reduced their habitats to expand our cities, meaning that encounters would inevitably become more frequent. It is now our duty to protect these animals and guarantee that they also have a place to live.

Our political group had tabled an alternative motion for a resolution (which further explains some of the arguments I mentioned in this article) to fight of this attempt to downgrade the protection status of wolves, and also to protect the rights and existence of upland pastoralists, who are custodians of enormous biodiversity in Europe thanks to low-intensity high nature value farming. Nevertheless, unfortunately, the other groups failed to share the same view.

On the bright side, the resolution adopted is a non-binding document – it only contains recommendations, which the Commission can choose to not consider when proposing legislation. Along with environmentalist NGOs, we now place our faith in the Commission’s judgment, which is expected to stand firm with science, protecting these magnificent living creatures.