“The idea that the US can retreat from the world and build a metaphorical wall around itself, is as implausible as the establishment consensus that the US should and can be involved in solving virtually every global and international problem.”

New York (Brussels Morning) The celebrations in American cities began Saturday morning as the news that Joe Biden had been projected as the winner of the election spread throughout the country. For millions of Americans, it was as if a psychic tumor had been removed. While millions of Americans were euphoric that Trump’s authoritarian aspirations have been, at least for now, stopped, Europeans were also pleased that Joe Biden will return the US to a more rational, and for our allies, recognisable, foreign policy.

President-elect Biden has a great deal of experience on foreign policy going back to his years in the senate. Unlike most recent presidents, with the exception of George H.W. Bush, Biden is familiar with the structures, ideas and key actors in the US foreign policy community as well as with foreign leaders, multi-lateral institutions and geopolitical challenges. This should, and by most accounts has, contributed to a sense of relief in the capitals of many American allies. However, that relief should be tempered by an understanding that while Donald Trump lost the election, neither he nor the support he had for a very different approach to American foreign policy has gone away.

Trump’s foreign policy was clumsy, poorly coordinated, and too frequently guided by Trump’s ignorance, sense of personal grievance and avarice. However, some of the guiding principles of Trump’s foreign policy, notably the notion that the US should be less engaged with the rest of the world, resonated with large proportions of the American people and, if articulated by a less toxic politician, can do so across party lines.

Two macro-challenges

Biden now faces two macro-challenges as he seeks to shift American foreign policy. First, he must undo the damage to America’s alliances and potential leadership in the world that was occurred during the last four years. This will require diplomacy, rebuilding relationships with our allies and repositioning the US as a country that can again contribute productively to addressing global problems like climate change and the Covid19 pandemic. These tasks will be made more difficult by the gravity and urgency of the domestic crises, around Covid, the economy and racism, that will greet Biden when he becomes president.

The second, and related, challenge that Biden will face is to rebuild a consensus among the American people that the US should be deeply engaged with the rest of the world. Over the years, the American people’s views on this question have fluctuated, responding to both domestic and international events, but this is a moment when the desire to engage internationally, due to Covid, the Covid related recession and lingering fatigue with what still seem like never ending wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, may be low or deeply divided along party lines with Democrats and Republicans wanting substantially different foreign policy approaches and priorities.

Biden’s task is to build something approaching a consensus for the same vision of America’s role in the world to the American people that the foreign policy establishment has tried, with deeply mixed success, to promote since at least the end of the Cold War. He will do this in the context of a Republican Party whose leadership in congress, particularly in the senate, is still more or less supportive of these ideas, but whose pro-Trump base is not. He will also do this in the context of international dynamics that are significantly different than they were when he left office for years ago.

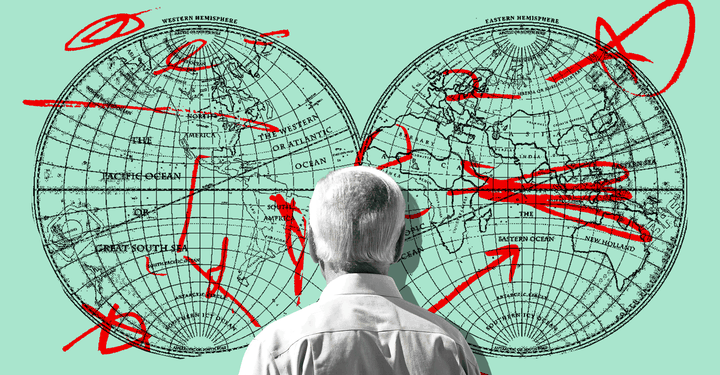

Looking out and seeing a mess

Biden and his foreign policy team are looking out at an international environment where Trump’s belligerence, contempt for traditional allies, fealty to Russian President Vladimir Putin and lack of any sophisticated understanding of the world has created a need for a restoration of previous international arrangements and approaches. However, tens of millions of Americans, from both sides of our deep partisan divide, look out at the world and see a mess, with Covid ravaging much of the globe, China’s ascension seeming unstoppable, Russia gaining ground in its efforts to destabilize Europe, rising racial and ethnic tensions and the usual intractable problems throughout much of the globe, and think the US should not get too involved. Neither side is entirely wrong, but the idea that the US can retreat from the world and build a metaphorical wall around itself, is as implausible as the establishment consensus that the US should and can be involved in solving virtually every global and international problem.

Given all this, it is very difficult to accurately predict what a Biden foreign policy will look like, but we know some things already. Biden will staff his foreign policy team with experienced professionals not with legislative back benchers like Mike Pompeo or corporate chieftains like Rex Tillerson. We also know that he will act cautiously and not be taken in by flattery from dictators, and that he will lean towards longstanding allies whose legitimacy comes from democratic elections rather than strongmen who wantonly disregard human rights. For that, at least, Europe is right to be relieved.