Madrid (Brussels Morning) As Europe was burning this summer, the term “climate change” came to people’s minds, pointing to a destiny that perhaps is unavoidable. Talking to scientists is empowering: a lot is being done and can be done. What happened need not continue happening. We can manage fire.

But that is not a challenge for the faint at heart. Over the last decade, four million hectares of forest and wooded land have been burned in Europe; that is an area larger than the territory of Belgium. This challenge is real, tangible.

The Mediterranean feeling

Stepping onto a balcony in the centre of Madrid, the sky looked ablaze. The temperature that Sunday topped 41C. The heat alone in Madrid is enough to pack up and leave for a city less concrete and less distant from the beach, but many don’t have the means to go. El Pais ran a great story on “climate refugees” here in Madrid, those who have no access to air conditioning or backyard pools who head to malls for the day where the temperature is required to stay below a certain temperature. If you closed your eyes, you might well have been in Sicily, which this year smashed Europe’s temperature record, hitting the 48.8C mark this August. You might have been in Greece, or in a number of places along the Mediterranean where climate was once part of the appeal. Perhaps no more?

The streets were empty, with half of the city out on vacation, and those who weren’t, somewhere they could get cool. I barely noticed the sky until sunset, keeping the shutters down on the windows to keep out the heat and when I finally did look out it was clear that there was nothing ordinary about the intense sunset that night. Indeed, just outside Madrid in the Castilla y Leon region, people were fleeing their homes and firefighters were hard at work to contain the flames. Watching the TV screen on mute, one could be fooled: is this Evia, Kabylie, Antalya, or Sardinia?

Fires erupt across the Med

This year’s fire season has ravaged the Mediterranean. July 2021 kicked off the season which will likely be seen as a spike. Stefan Doerr, Director of the Centre for Wildfire Research and Professor at Swansea University tells Brussels Morning that while this year has been bad, reporters must be careful not to proclaim this year as the worst, as one needs to be consistent in comparisons. Europe has in fact been on a downward trend in terms of total area burned per year, though he is concerned this year may change that. Also where fires occur, they have become more destructive in some regions.

At least 69 people died in Algeria, and thousands across Turkey, Greece, Italy, Spain and France were evacuated from their homes. Following the release of the IPCC Climate Change 2021 report, it is becoming increasingly difficult to avoid the science telling us these once in a lifetime disasters and increasingly extreme weather conditions are a direct result of human activity influencing climate change.

Today, climate and environment are inherently political. Environmental security is increasingly becoming a bigger risk for millions, and what has happened across southern Europe this summer has highlighted the dangers of only reacting to disaster rather than averting risk. Speaking with fire and meteorology experts and the European Commission, it is clear there is a gap between knowledge and execution, though it cannot merely be described as a political misstep. Humans start fires and so does nature. What can be controlled is how the landscape is prepared and citizen education, to ensure minimal casualties.

Fire is more about people than nature

While increasing frequency and severity of many natural disasters can be directly linked to climate change, the various impacts and feedback loops of wildfires have been underrepresented in climate talks, risk reduction agendas and policy frameworks noted Lindon Pronto of the European Forest Institute. Unlike a tornado or a hurricane, fire’s “destructive” capacity does serve an ecological purpose and is often necessary and benefit fire-adapted landscapes. But this makes it a more complicated challenge for the decision-making community to respond to. In the US, Native Americans learned to live with fire and often have used it to their benefit. However, as a rural living exodus has occurred across the Mediterranean and Western US, living with fire seems to be an impractical reality, because the previous systems which made the fire-balance sustainable is no longer there.

With fire, it seems we mostly stand around and wait for the show to begin. This is in stark contrast to how we deal with other natural disasters that are less predictable, but receive larger relief budgets. Fires are predictable, Pronto explains, and therefore preventable to some extent. Doerr notes that fires are just not on an equal footing in terms of destructive capacity and death tolls as other natural disasters, although they have a huge economic impact and people lose homes and livelihoods.

This is a notion that is being challenged thanks to the economic, environmental and social impact of recent extreme events.

Pronto muses that “much of the challenge with the wildfire problem is that is largely of our own doing, it’s extremely complex and very much a socio-ecological interplay. I would even argue that it’s not better fire management we need, but better people management.”

European Commission officials echo this sentiment, stating that over 95% of fires are started by human action. Among some of the most important projects related to climate change that the EC is taking on is the Green Deal, which will include “climate proofing and resilience building” and maintains that “prevention and preparedness is crucial.” So how does one need to actively prevent and prepare?

This year’s fires, every year’s fires

The wild temperatures in Madrid aren’t an anomaly this summer. Brussels Morning spoke with Costantinos Cartalis, Director of the Department of Environment Physics at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and former Member of the Scientific Committee of the European Environment Agency. Greece itself experienced devastating fires that raged for a month this summer, leaving people desperate and without homes. The Prime Minister even created a new portfolio, giving Europe the first “fire minister.”

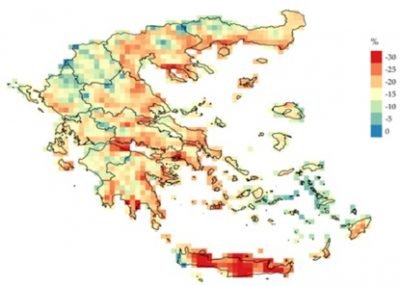

The catastrophic forest fires that hit Greece, and the Mediterranean in general, in August 2021 are undoubtedly associated with the fierce heatwaves in intensity and duration recorded in Greece and the wider geographic region. Their impacts, as far as burned areas are concerned, reflect gaps in the fire prevention policy currently under implementation.

Climate simulations for the decades to come show that changes in three climatic factors associated with forest fires, namely the increase of air temperature as well as the decrease of precipitation and soil moisture, are expected to intensify forest fires. To these we must add projections for more intense and frequent heat waves, which create extremely dry flammable {biomass} material, contributing to the ease (in which) forest fires (begin) and their rapid spread, while adding to the difficulty of extinguishing.

It is therefore obvious that Greece, as well as the rest of the Mediterranean countries, have to as first priority, modify their fire prevention plans in order to deal with an explosive mix of climatic conditions leading to more and more aggressive forest fires.

Policy for Prevention not just protection

So what does better fire prevention policy look like? Pronto has chaired the Landscape Fire Crisis Mitigation group of the Fire-IN project, auditing firefighting capability gaps across Europe, later putting together a thematic policy brief for the European Commission: “Wildfire problems occur at multiple levels. We know we can’t change the climate or the weather, so our best chance is to deal with fuel (vegetation management), influence human behaviour and adapt our new, built infrastructure to be more resistant and resilient to fire. These three areas should be addressed independently and together – always observing the context.”

The Med’s fire fuel issue

Experts point to the native pine trees of the Mediterranean landscape. Doerr points to the fact that some countries have in the past encouraged the planting of very flammable trees such as Eucalyptus in Portugal and Northern Spain, which only need about 8-12 years to reach commercial maturity. Replanting with pines or eucalyptus can be dangerous and countries, experts argue, should take a long view. While less flammable trees such as cork oaks or olive trees take many more years to grow, there is more consistent economic return in the years following and they are system that is able to sustain its environment.

Rural Exodus leads to a need to incentivise living outside cities

Another land management technique is incentivising a return to the land of sorts. Across the Mediterranean, there has been a shift of population density to the cities, referred to in Spain as España Vaciada. Leaving behind abandoned or sparsely populated villages means that land managed for centuries is now more at risk of fire. Since the exodus, much of this land has become overgrown and unwieldy. Pronto and Doerr both argue for more intensive land use through farming, silviculture, and livestock, which makes landscape more fire resistant.

Europe prepares for the fight

In a written statement to Brussels Morning, a European Commission spokesperson recognises that “wildfires and climate change are closely linked in a vicious cycle,” a challenge that raises issues of greenhouse gas emissions (carbon dioxide), as well as causing flash-floods, landslides, and desertification. That is why fire is a priority on “climate action,” a budget line to which the EU has pledged 30% of its 2021-2027 budget.

The Commission has analysed the potential threat that climate change may bring to Europe in the recent study “Peseta IV”, which shows that the number of days in which fire danger will be very high or extreme will increase with climate change. The Commission set up in 2019 RescEU, a revised Union Civil Protection Mechanism that is already facilitating the collaboration among countries on firefighting and funding additional means for combating wildfires in the EU and neighbour countries. Furthermore, the Joint Research Centre of the EC has developed and operates the European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS), an early warning and monitoring system, that is currently part of the EU Copernicus programme and is one of the most advanced systems of its type. A similar system, the Global Wildfire Information System (GWIS), is already in place and complements EFFIS in areas outside the EU.

In short, we are preparing for this battle. But we could do things differently, and better.

Pyromimicry: the recipe for life

Pronto ended his discussion with BM with a recipe for life that could be extended to firefighting:

“After 3.8 billion years of [nature’s] research and development, failures are fossils, and what surrounds us is the secret to survival.’ So, if we are to live in fire resilient communities, we had better start designing them in accordance to the underlying ecological and geophysical landscape on which they are built upon. To facilitate this, I petition to introduce a new concept – Pyromimicry – and define it as such: The aim to achieve and design fire-resilient landscapes and built-environments by emulating the structural, organisational and adaptive characteristics of fire tolerant ecosystems and the species thriving therein.”

It is true that we can invest heavily in firefighting techniques, but the failure seems to lie in the socio-political and economic realities of an increasingly urban world. More planes can be bought, but inaction and lack of education to address the roots of the issue will leave Europe fighting an uphill battle.

It is said that being crazy is to repeat the same action in the hope that it will churn different results. Time to wise up and listen to science.