Stop-gap measures to protect communities and housing during the pandemic are potentially delaying a an inevitable crisis. Brussels Morning explores examples in London and Lisbon.

London (Brussels Morning) London is well known for its multicultural tapestry with entire streets and postcodes dedicated to rich and unapologetic expressions of South Asian, African, Caribbean and Middle Eastern traditions — the food, textiles and other cultural fare forming the heart of communities, built over time.

The Latin community may not have the same long association with Britain’s most well-known melting pots, some of which arose in the late 19th century, but with decades of new migration it is fast becoming known as one growing in the UK and that is potentially vulnerable. Recent events have seen spaces that have become community stalwarts, taken away and placed under threat.

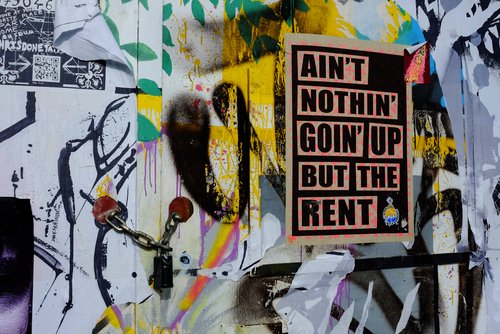

Stop-gap measures to stem the financial impact of COVID-19 could now be delaying the inevitable demise of the remaining hub of the Latin community in London, giving way to new housing developments grown out of market forces that have plagued cities throughout Europe. The pandemic, some say, could be incubating a crisis waiting to happen.

Pueblito Paisa

Internationally, reports have covered one particular corner of Britain’s capital that serves the UK’s Latin American diaspora — Pueblito Paisa, also known as the Latin Village, a market with a high concentration of shops and businesses owned or run by Latin diaspora in Seven Sisters, North London.

The high-profile regeneration programme that would see the market closed during redevelopment has even gained the attention of the UN, with an intervention warning that the compulsory purchase order (CPO) — a legal function in the UK that forces through the sale of land or property irrespective of consent — of the market would have a “deleterious impact on the dynamic cultural life of the diverse people in the area”. Regardless, the CPO was approved by the government in 2019.

“The UN cannot force the government to do something, they can only advise and explain why [a people] have been mistreated and why this is a human rights violation”, said Victoria Alvarez, one of the traders in the market and campaigners who say the redevelopment would result in traders losing their business due to inevitably higher rents.

A planning obligation, however, has compelled Grainger, the private developer gifted the regeneration contracts, to fulfil certain conditions. Business owners and Grainger have been involved in ongoing consultations with stakeholders to iron out the move to a temporary location, one that might benefit the traders, rather than placing them at risk of losing trade.

A pan European problem

In many ways, issues around Pueblito Paisa replicate similar stories, not just around London or the UK, but across Europe. Schemes to reinvigorate less invested-in areas and commerce have all led to the gentrification process that causes displacement. Even tech innovations like Airbnb have triggered rental increases in many locales like Lisbon, Portugal.

European states have responded in varying ways — rent freezes in Berlin, Germany and a draft housing bill in Portugal that promises housing for all. Solidarity movements and working groups have also emerged in trying to assert a Europe-wide solution.

The pandemic, however, has made more prominent the inequality in housing policy, say experts. On one hand this has forced stop -gap measures to protect people from losing their homes. On the other hand, there are fears these will delay the inevitable. The overarching urgency is for changes to be made at a policy level to prevent systemic harm.

Luis Filipe Goncalves Mendes — a researcher at the Institute of Geography and Spatial Planning of the University of Lisbon and a member of Morar em Lisboa, a community action group in Lisbon for fairer access to housing — says evictions, which had been escalating to untenable levels prior to Portugal’s housing for all initiative, have now halted, particularly due to the pandemic, which many associations and grassroots groups seized upon to argue the necessity for affordable housing.

After all, no one can quarantine without a home to stay in, said Mendes, and they can do so in Portugal until June 2021 when the current moratorium on evictions end.

“We’re very afraid of what will happen after that”, confides Mendes, “postponing the moratorium is just a way to postpone a structural problem that the state is not taking care of, which is a housing problem”.

Mendes explained to Brussels Morning that there have been a number of positive steps during this period, including landlords not being able to revise contract terms. The city has also taken over some leases and rent caps have been put in place. One of the proposals touted by the government, however, is to give people access to loans to help pay rent arrears, but the measure was criticised for being unnecessarily bureaucratic, says Mendes, as it would potentially exclude thousands of vulnerable and marginalised parts of society, including the elderly or migrants.

It is a crisis yet to happen, he said, “they will simply overcharge tenants later on”.

A moratorium on evictions has taken place in other European countries as well, such as in Spain and France, but mechanisms to regulate housing in rental markets differ country-to-country.

The future of Latin Village

Since the onset of the pandemic, steering committee meetings involving traders in the Latin Village have moved online, but continued consultation and managing the continuity in income has been rocky.

Markets had initially closed when the UK went into national lockdown but most reopened as they were considered to sell essential goods.

The Latin Village remained closed, however, deemed too much a health and safety hazard to reopen.

“They never invested any money in the market”, said Alvarez, referring to Market Asset Management (Seven Sisters) Ltd (MAM), the market operator that leased the property from Transport for London (TfL) — the official landlord of the site and one of London’s largest landowners as well as the body responsible for mobility in London.

Even before the market closed, traders were having a hard time with electricity cuts, says 22-year-old Viviana Da Silva, who grew up in the market as her mum toiled as a hairdresser and eventually business owner.

This later emerged as a result of MAM’s non-payment of energy bills as an unlawful abstraction of electricity from a neighbouring building, an offence in English law.

Traders were asked to pay the service charges regardless, says Carlos Burgos who runs the Seven Sisters Development Trust. At the same time, the market suffered power failures and many business operators were threatened with eviction. Alvarez as well says she and many of her colleagues were met with racially charged language.

Community loss

Grainger has insisted the Latin community remain in plans for the future of the area. But Burgos says the rent-free period — being offered at the temporary site — or affordability, won’t last long, estimating rent will go up 300% eventually, delaying an inevitable impact to the community.

MAM is owned by Quarterbridge, specifically dedicated to acquire, develop and operate markets and food halls. It’s one of many within the overarching organisation’s network of companies, which has ambitions to redevelop markets all over the UK. Despite long-standing grievances against it, it has been in Grainger’s plans to keep the company as a market manager.

The list of complaints finally landed on TfL, which took back ownership of the lease. After seven months of back and forth the local government body offered a financial support package to the traders. TfL communicated to Brussels Morning it understood that MAM was considering liquidation although it is currently still active. It is not clear if any of the other companies under Quarterbridge will be involved in the future of the market.

In a response to Brussels Morning, Graeme Craig, Director of Commercial Development at TfL said:

“Small and independent businesses, like those at Seven Sisters Market, are vital to London’s economic recovery and we’ve been doing everything we can to help them start trading again safely.

“Unfortunately, despite working for several months to enable Seven Sisters Market to reopen in some form – including investigating a new temporary market – we reached a point late last year where the scale of works was such that we could not be sure the market would reopen before its planned move to Apex Gardens, the new temporary market being delivered by Grainger as part of its wider redevelopment plan.

“We understand how disappointing this is for traders and the local community. We’re continuing to focus our efforts on supporting traders, including essential works on retail units on the High Road so they can operate safely and legally, and the Mayor is also supporting TfL in providing direct financial assistance to the traders.”

Brussels Morning asked Quarterbridge about its potential future in the market and its handling of disputes but the company denied any role in managing the Latin Village and declined to comment despite Market Asset Management (Seven Sisters) Ltd (MAM) being its offshoot.

On asking Grainger about future rental costs, Brussels Morning did not receive a response but the information on the company’s website indicates no plans for ‘affordable housing’ or ‘social rents’ for the 149 units to be built on the acquired land, in addition to the market.

“Communities like our community keep losing important places”, Alvarez said to Brussels Morning, referring to another recent loss for the community in the south of London as the Elephant and Castle shopping centre, home to many Latin American businesses, closed to clear the path for a huge redevelopment plan.

Brighter future for housing in Europe?

Amid concern for the immediate future, there has been some light at the end of a long tunnel, at least for housing. The European Parliament recently approved a report on Affordable Housing, that Mendes himself fed into, a milestone for the bloc.

Marie Linder, President of the International Union of Tenants (IUT), which oversaw the report said it at least raised the red card against speculation and for the need to overcome investment barriers.

“National governments still believe that the market will solve all housing problems”, she said, which has had devastating effects.

The housing for all initiative won’t touch the Latin Village, however, with Britain’s exit from the EU firmly excluding the UK government from falling in line with standards proposed in Brussels.

Meanwhile, large players like Grainger, one of the biggest private landlords in the country and on the FTSE 250 index that brought in 270 million pounds of revenue in 2018. In the last quarter of that year, it also acquired the multi-million-pound GRIP REIT (Real Estate Investment Trust), forecasted to grow to a portfolio-size of 3,000 properties worth over 1 billion pounds.

It makes the task of saving Latin Village a battle seemingly of David versus Goliath proportions.

In some ways, Da Silva believes the pandemic was used as an excuse to finally close the market but still hopes it is not permanent:

“It is such a unique place for not just the traders but for the Lain community to go in and be in a place that reminds them of home”.